- | 3:00 pm

These color-changing, energy-saving windows are inspired by an unlikely sea creature

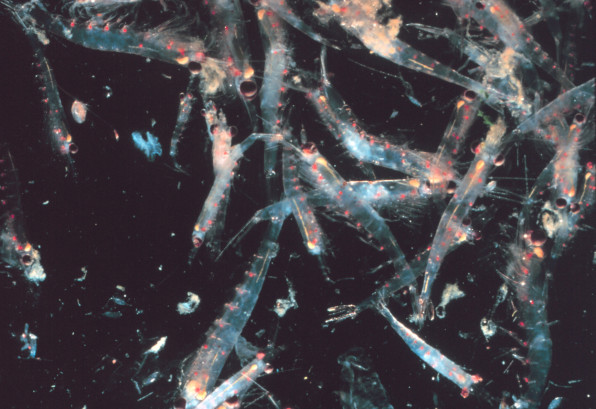

A team of scientists has developed a groundbreaking material that mimics krill, using oil and colored water to change its opacity in a matter of minutes, which could change how buildings heat and cool themselves.

If you know anything about krill, it’s probably from a childhood lesson about what whales eat, but there’s actually a lot more to the little translucent crustaceans than just being a food source. When they’re not being vacuumed up by whales, they can actively change the color of their skin (from transparent to opaque) in order to protect themselves from the sun. And now, a team of scientists at the University of Toronto believes that building facades could do the same.

They’ve designed a new ultra-thin material that could be applied to the surface of windows and act as a highly customizable skin, which can change its opacity in a matter of minutes. Their work was recently published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, and though the concept is in its very early stages, it suggests the very urgent, very real need for architects to design dynamic buildings that can adapt to the changing climate—without the need for mechanical add-ons.

The market is already full of such add-ons. From simple shutters and motorized blinds to high-tech “smart windows” that use low voltage or heat to change their tint and opacity, the solar-shading industry has decent enough options. But few of them, aside from very expensive smart windows, tackle the root of the problem, namely the fact that up to 35% of a building’s energy is lost through its windows. “Windows are horrible as they’re designed, but they can be remarkably efficient if they’re adaptive,” says Raphael Kay, a mechanical engineering graduate student and author of the study. So, what if, instead of pulling down the blinds and blasting the AC in your office, you could let your windows automatically adjust to the level of sunlight using nothing but water and cheap oil fluids?

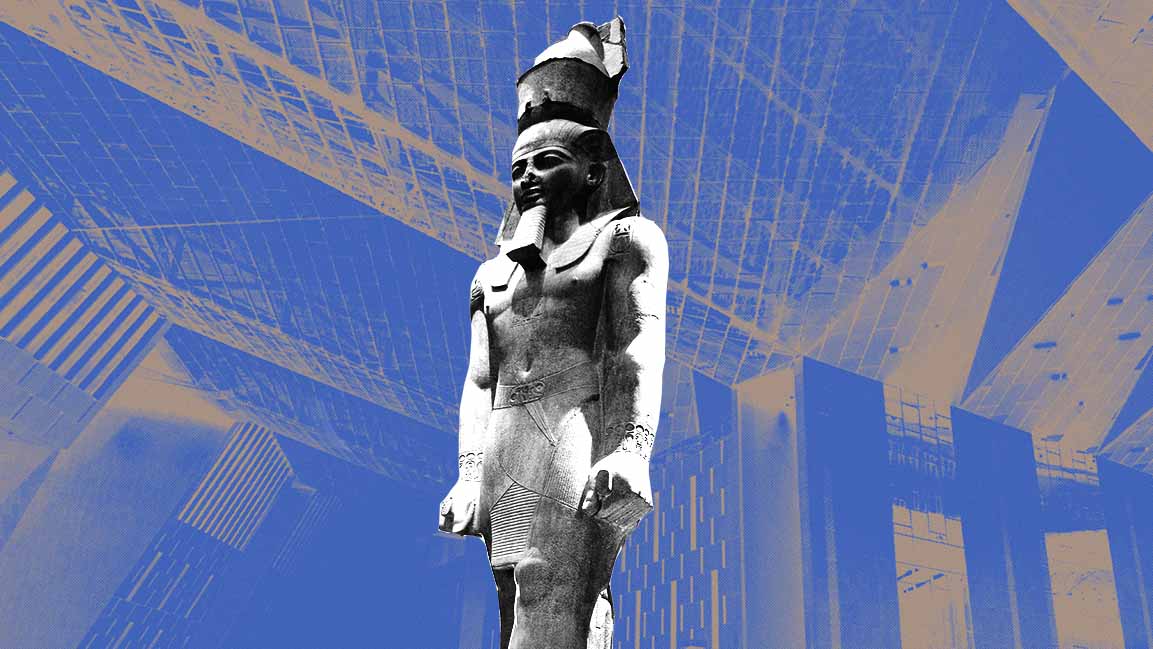

The idea is rooted in biology yet applicable to the built environment. Animals have spent millions of years adapting to varying ecosystems and climate change. Humans have adapted, too, yet our buildings haven’t followed the same trajectory. “It’s weird the way that buildings are so static,” says Benjamin Hatton, a professor of materials science and engineering at University of Toronto, who supervised the study. “In biology, that would be very unusual.”

Imagine a composite material, less than a 1/4-inch thick, that’s made of a fluid sandwiched between two solid but transparent sheets. Now imagine that the fluid is actually two fluids: the “host fluid,” which is always there, and the “guest fluid,” which is what allows the changing levels of transparency. In the same way that krill sends pigment particles through a network of channels on its skin, the guest fluid (colored water) would flow through the host fluid (transparent mineral oil). And because water and oil don’t mix, the water would push the oil away, take up more space, and result in a darker window. As for the oil, it would either flow into four “bladders” on each corner of the material, or it would swell inside the two sheets, provided they’re made of a flexible material, like silicon.

In a computer simulation, the team found this system to be up to 30% more efficient compared to motorized blinds and smart windows. So, when the midday sun is beating down on your desk, you could dim the window and keep your space cool; and when it sets, or a summer storm rolls in, you could lighten it back up.The advantage of the fluid system is an extreme level of precision. Most shading systems are binary: you roll blinds up or down and flip shutters open or closed. But fluid-controlled windows would be like closing and opening hundreds of tiny blinds at different times of day and in different locations across a windowed façade. To borrow another biological analogy: an octopus has more neurons on its tentacles than in its brain, which allows “amazing levels of control right at the skin,” says Kay. Translate that to a building, and instead of a central “brain” guided by radiators, air conditioners, and other mechanical systems, you have firsthand control right on the skin, aka the facade.

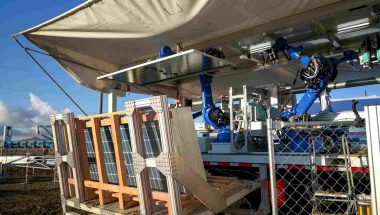

The idea presents a few challenges before it could actually show up in a building, mostly around the infrastructure necessary to control those fluids. The team envisions that each pigmented pattern—or bloom—would be controlled via a computer-powered digital pump: Adding more colored water would make the bloom larger (and the window darker), removing water would make it smaller. “The combination of what our material can do and what digital and AI can do, if we bring these together, you can imagine a skin that can do anything you want,” says Kay.

For now, the scientists have built a prototype the size of a windowpane. Next on the list? Hiring “an army of undergraduate students” and figuring out how to scale this up to a point that transcends windows. “If you can make a window better thermally, there’s no reason to have windows separate from walls,” says Kay. In other words, architects could turn entire facades into adaptive skins that can take on various properties—from living art murals, to windows that can adapt to our circadian rhythm by taking on different hues depending on the time of day.

All of this thanks to a tiny little creature that happens to be the whales’ favorite snack.