- | 9:00 am

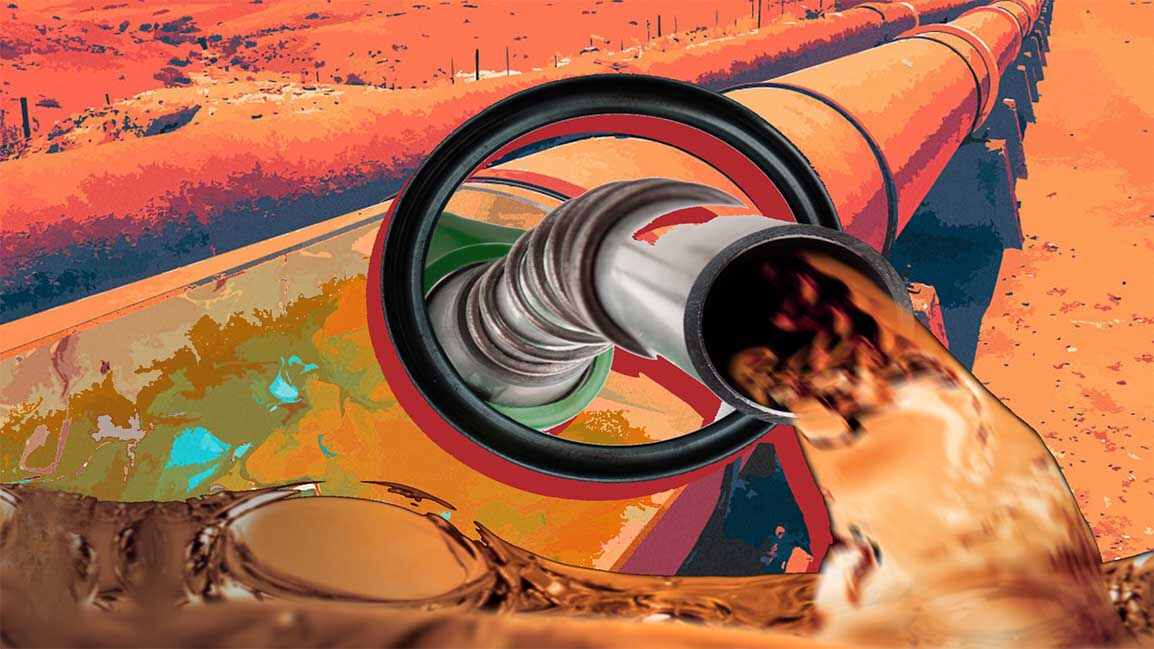

Is the 1973 oil crisis back? How will it impact the Middle East?

International oil prices have fallen since the March peaks, and in such a situation, experts say OPEC+ sees no logic in adding oil to a falling market.

“Sorry, No Gas” handmade posters across fuel stations pop to mind thinking about when the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposed an oil embargo almost half a century ago. What came to be known as the 1973 oil crisis was a significant event in the history of the Middle East, and we might see its second version if we don’t treat it carefully. It was the Yom Kippur War then and the Ukraine-Russia war now.

The embargo enforced by OPEC shocked the petroleum industry. The International Energy Agency (IEA), founded in the aftermath of that crisis, compelled industrialized nations to build up strategic reserves in case of supply disruptions in the future.

Today, it seems history is repeating. Fuel shortages and blackouts have caused economic turbulence in import-dependent countries.

After more than 70,000 protesters filled Wenceslas Square in the Czech Republic to express their anger over soaring energy prices last week, more people living in Europe, including France and Germany, are taking to the streets to protest against the energy crisis.

Earlier, acute shortages and days-long lineups compelled authorities in Sri Lanka, which was already collapsing under the escalating crisis, to issue work-from-home orders. Protests over rising prices have shaken Panama and Pakistan. These countries resorted to cutting their work week to relieve pressure from protracted power outages.

High oil prices have been destabilizing the global economy for months, and analysts warn that there is no end date as long as the conflict in Ukraine continues. Nevertheless, it seems as if the war has unmasked an already existing crisis, says Michelle Foss, a fellow in energy, minerals and materials at Rice University’s Baker Institute.

During the pandemic, there was a sharp drop in consumption of gasoline, jet fuel, other fuels, and electric power, and there was a call for the “end of oil”. “As a result, when Russia invaded, the market reactions exacerbated pressure already building on oil and gas prices because demand had recovered way beyond what was expected,” says Foss. “We were worried about this – to our credit, most of us at Baker Institute felt that consumer responses were temporary and that we would see tight supply-demand balances as we all emerged from forced lockdowns.”

The US, Europe, and Japan have put pressure on OPEC, the 23-nation organization led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, to increase supplies. After Biden visited Saudi Arabia in July to press for extra oil to cool international markets, analysts had speculated OPEC+ would increase supply. This is questionable as the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman, announced that production capacity will be expanded to 13 million barrels per day only. The message to the world is that OPEC makes the final decision on oil supply.

However, a recent Reuters report says that OPEC leaders Saudi Arabia and the UAE are ready to deliver a “significant increase” in oil output should the world face a severe supply crisis this winter.

Fears of a recession have caused oil prices to decline by almost 25% from recent highs. At this point, increasing oil output will only make the market worse. Additionally, due to the pressure from the green energy movement to use alternative energy sources, most businesses are reluctant to invest in the oil industry, which is not helping the severe shortage of oil worldwide, the head of Saudi Aramco said in the World Economic Forum 2022 in Davos, thus production cannot increase any faster as promised.

Meanwhile, many countries in the Middle East consider the failure to address the region’s climate crisis – pressing water scarcity and persistent droughts – a national security concern. As per the EcoPeace Middle East report, climate change can also be seen as a multiplier of opportunities in the region, where one or more nations may view the challenges posed by climate change as a chance to evaluate current policies.

To solve the energy crisis, the EU signed a green transition framework in June to enhance gas imports from Egypt and Israel. East Mediterranean gas will be processed and delivered to Europe. In the long run, Europe will receive renewable energy, primarily solar energy, produced in the enormous desert landscapes of Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf.

To free up capacity for more valuable exports and position themselves as partners to European markets in the energy transition through green hydrogen, some GCC nations, like Saudi Arabia, emphasize the use of natural gas and solar energy. Saudi Arabia aims to generate 50% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030.

The motivation for Saudi Arabia to speed up its renewable energy installations comes from the fact that it relies entirely on fossil fuels for its electricity which has put the country ahead of the global average (standing at 62%) for fossil generation share as per Ember, a data-driven, energy think tank.

It is not easy to go green – it’s time-consuming and expensive. Given that alternative energy is material intensive, this means that sharp increases in prices for plastics (more expensive oil and gas) and metals will increase costs for equipment and projects and erode the market value of companies.

And not just for wind and solar developers but also for battery producers—there’s a sharp increase in EV pricing.

“Over the past few months, there’s been a wake-up call on how difficult it will be to use wind and solar, or anything else – all of the alternative energy tech ideas have the same problems of scale, materials intensity, performance challenges,” says Foss.

Meanwhile, international oil prices have fallen since the March peaks, in part as high prices have limited consumption. In such a situation, experts say OPEC+ sees no logic in adding oil to a falling market.